The Hidden Cost of ‘Just This Once’ - How Small Compromises Erode Engineering Standards

In the high-pressure environment of modern software delivery, there is a phrase that carries more weight than any architectural diagram or complex algorithm. It is whispered in late-night Slack channels, suggested during tense sprint reviews, and voiced in the final hours before a major release.

“Can we just do it this way, just this once?”

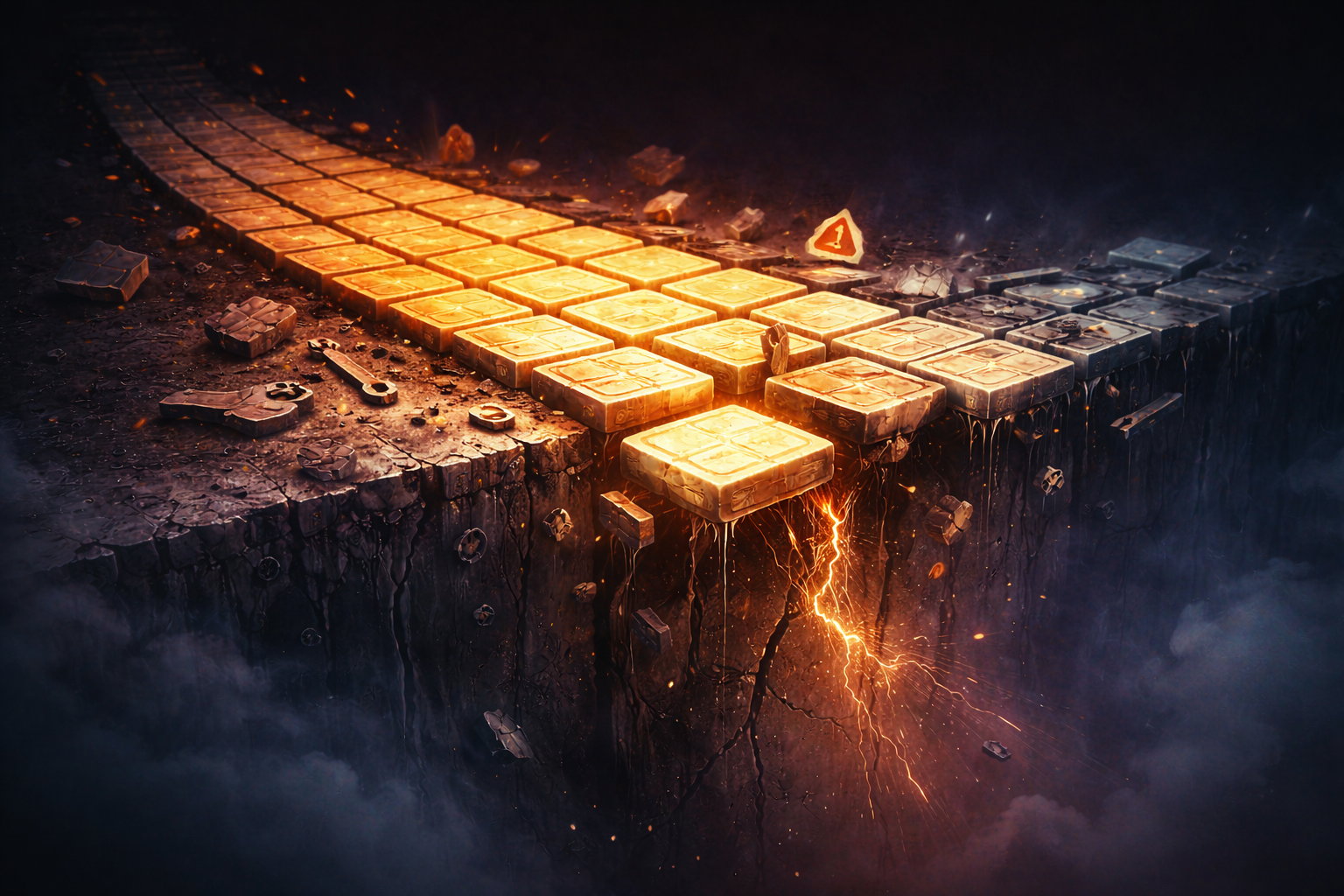

On the surface, it sounds like the height of pragmatism. It’s a temporary bypass, a minor detour from the “ideal” path to meet a very real business need. But in the world of engineering, "just this once" is the most dangerous phrase in our vocabulary. It is the first crack in the dam, the initial concession that begins the slow, silent transition from a culture of excellence to a culture of "good enough."

The Most Dangerous Phrase in Engineering

Few phrases sound as harmless and prove as destructive as “just this once.”

It usually appears under pressure. A deadline is close. A release window is narrowing. A customer escalation is loud. In that moment, the phrase feels pragmatic, even responsible. After all, the intent is not recklessness; it is delivery. The compromise feels contained, temporary, and reversible.

And that is precisely why it is dangerous.

Small exceptions rarely announce themselves as turning points. They arrive quietly, wrapped in good reasons. They feel isolated — an anomaly rather than a shift. No one believes they are lowering standards; they believe they are navigating reality.

Yet, in engineering, the deepest damage is rarely caused by dramatic failures. It is caused by a series of small, justified compromises that slowly redefine what is acceptable. The paradox is simple and uncomfortable: the smallest compromises often cause the deepest long-term erosion.

This article is not about perfectionism. It is about professional discipline about understanding how standards decay, not through negligence, but through repeated acts of rationalization.

Compromise Is Rarely Technical, It Is Behavioral

When engineering standards slip, the instinct is to blame technical constraints: legacy systems, tight timelines, inadequate tooling. These factors are real, but they are rarely the root cause.

Standards erode because of behavior, not limitations.

Most teams can do the right thing. They choose not to, often for understandable reasons. The key distinction lies between conscious trade-offs and rationalized shortcuts.

A conscious trade-off is explicit. It acknowledges cost, impact, and risk. It is framed as a deviation from the ideal, not a redefinition of it. A rationalized shortcut, on the other hand, reframes the compromise as harmless or necessary, minimizing its future consequences.

Intent plays a deceptive role here. Engineers focus on why they are making the compromise — delivery pressure, customer urgency, leadership direction. What gets ignored is impact: how that compromise will shape future decisions, expectations, and behaviors.

Intent soothes the present. Impact accumulates in the future.

The Psychology of Justification

The phrase “just this once” does not emerge in a vacuum. It is enabled by predictable psychological forces.

Deadline pressure is the most obvious. When time is scarce, discipline feels like a luxury. The focus narrows to immediate outcomes, and future costs are discounted.

Social permission reinforces the behavior. When peers agree, the compromise feels normalized. When multiple people say “it’s fine,” resistance feels pedantic rather than principled.

Authority bias plays a significant role. When a lead, architect, or manager approves an exception, it gains legitimacy. The decision is no longer personal; it is sanctioned. Responsibility diffuses.

Over time, these forces lead to a phenomenon well-known in safety-critical systems: normalization of deviance. What was once an exception becomes routine. The baseline shifts, not through debate, but through repetition.

Exceptions quietly rewrite what “normal” means.

From Exception to Precedent: How Standards Actually Erode

Engineering standards rarely collapse in a single moment. They erode incrementally.

The first exception is memorable. It is discussed. It is justified. It feels special.

The second exception references the first. “We did this last time.” The third exception barely registers. By the fifth, it is no longer an exception — it is precedent.

This is how standards actually change: not by decision, but by drift.

Each compromise lowers the psychological barrier for the next one. The cost of resistance increases. What once required debate now requires justification to avoid. Teams rarely notice the exact moment the standard slipped because there was no explicit decision to change it.

Invisible Costs That Surface Later

The true cost of small compromises is rarely visible at the moment they are made. It appears later, often disconnected from its cause.

One cost is cognitive load. Future engineers must understand not only what the system does, but why it violates its own rules. Every exception adds mental overhead, making the system harder to reason about.

Another cost is fragility under change. Compromised systems often work until they are modified. During incidents or urgent changes, hidden shortcuts surface as unpredictable behavior.

Perhaps the most damaging cost is the loss of trust in the codebase. When engineers stop believing that the system reflects deliberate design, they become cautious, slower, and less confident. Velocity drops because of fear.

These costs rarely show up on delivery metrics. They do not appear on dashboards. They emerge as fatigue, hesitation, and institutional memory of “this system being risky.”

The Difference Between Trade-Offs and Excuses

Not all compromises are failures of discipline. Engineering is inherently about trade-offs. The distinction lies in how those trade-offs are handled.

Responsible trade-offs share several characteristics:

- They are explicit and documented.

- They acknowledge cost and risk.

- They are isolated, not spread.

- They include intent to revisit or retire the compromise.

Excuses, by contrast, are implicit. They rely on verbal agreement, collective amnesia, and optimism. They downplay future impact and frame the compromise as inconsequential.

Professionals understand that constraints are real—but so are consequences. Discipline is not about refusing compromise; it is about refusing denial.

Discipline as a Personal Contract

At its core, engineering discipline is not enforced by tools, reviews, or policies. It is internal.

It is the standard you hold when no one is watching.

Professional engineers operate with a personal contract: a commitment to clarity, responsibility, and long-term thinking. This contract is not about heroics or perfection. It is about self-respect and about knowing that your work will outlive your presence.

Craftsmanship emerges when engineers ask, “Would I be comfortable inheriting this decision six months from now?”

Discipline is choosing the harder right over the easier now, repeatedly.

Team Culture: What Gets Tolerated Becomes the Standard

While discipline begins personally, it is reinforced or undermined collectively.

Leaders play a crucial role, often unintentionally. When exceptions are approved without acknowledgment, they become invisible endorsements. When speed is praised without regard to sustainability, shortcuts feel rewarded.

Silence in code reviews is also a signal. When questionable decisions pass without comment, the message is clear: standards are negotiable.

Over time, tolerated shortcuts shape team identity. Teams stop asking, “Is this right?” and start asking, “Is this acceptable here?”

Building Resistance to “Just This Once”

Preventing erosion does not require rigidity. It requires friction.

Healthy teams make exceptions visible. They name compromises explicitly. They treat deviations as temporary, not absorbed.

They create cultural norms where saying “we should not do this” is respected, not resisted. Where discipline is framed as professionalism, not obstruction.

Most importantly, they revisit compromises. Temporary decisions that are never re-evaluated are permanent in practice.

Resistance to “just this once” is not about saying no — it is about saying not quietly.

Conclusion

Engineering standards rarely fail in dramatic fashion. They are worn down through repetition, rationalization, and silence.

Every small compromise feels insignificant on its own. Together, they define the trajectory of a team, a system, and a profession.

Professional discipline is not a single act of integrity. It is the accumulation of small decisions made consistently over time.

Disclaimer: This post provides general information and is not tailored to any specific individual or entity. It includes only publicly available information for general awareness purposes. Do not warrant that this post is free from errors or omissions. Views are personal.